Milliún Dollar Leanbh

***This Review Contains Spoilers***

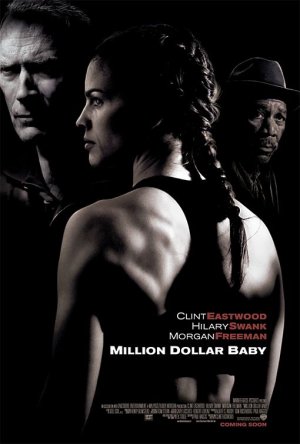

Million Dollar Baby is a movie I find works on different levels between first and second viewings. On my first viewing, I found the majority of the film great until the plot’s shocking and hard-to-digest turn of events in its final act – it ranked as one of my new favourite films of all time. On second viewing, however, I found Million Dollar Baby substantially even better as I was waiting in dread for the proceeding events; I mean almost literally quivering in fear knowing that dreadful scene is coming, that in which Maggie Fitzgerald (Hillary Swank) is knocked to the ground during a fight and her neck lands on the side on a stool (thanks to this motion picture I now fear the very sight of a tiny stool, scarier than anything in a horror film). Million Dollar Baby is one of the most emotionally draining films I’ve ever witnessed. It’s such a powerful experience I can’t just immediately bring myself to watch another film right away and I’ll still be thinking about it for days afterwards – a film so absorbing I don’t want it to end.

Clint Eastwood has only become a better director over time, in particular during the 2000s when he produced an impressive streak of directorial efforts with stories of unpretentious human emotion. His direction on Million Dollar Baby (as well as many of his other films) is astounding in how he makes the art of filmmaking look easy. He’s not a Martin Scorsese incorporating fancy camera and editing tricks, rather his films are presented in a simplistic and humble nature, often alongside a demure acoustic guitar score. Never has the presence of a fighter training in a darkly lit gym ever looked so immaculate as if it were a cathedral with the picture’s heavy use of shadows, stunning silhouettes alongside shots in which you only see the actor’s head (similar to those of Marlon Brandon in Apocalypse Now). Million Dollar Baby is one sweaty and grimy film, with the run-down gym known as the Hit Pit acting as a character in itself (especially since it doubles as a home for Morgan Freeman’s Scrap).

Eastwood has the ability to combine serious drama and subtle humour perfectly. As Frankie Dunn, I love his smart-alecky sense of humour such as the scenes in which he trolls a catholic priest, Father Horvak (Brían F. O’Byrne) with various theological questions for his own amusement while the banter and one-upmanship between Frankie and long-time friend Eddie “Scrap-Iron” Dupris are a real joy to watch. The gruff nasally sarcasm of Eastwood and the deep baritone voice of Freeman makes for a great combo of dry wit when they have conversations such as that regarding the holes in Scrap’s socks. However, the best comedy in Million Dollar Baby comes from the almost sitcom-like set-up involving the comic relief character of Danger Barch/Dangerous Dillard (Jay Baruchel). The very low-intelligence but well-meaning hillbilly just hangs around the gym every day without paying any membership and constantly speaks in an earnest manner about how he is going to become the boxing champion of the world while Scrap acts as his surrogate babysitter – comedy gold. Watching Million Dollar Baby again, I did get a massive laugh at the character’s introduction with his casual and innocent use of the most taboo word in the English language – a perfect summary of his character.

Surely it is an accepted fact that a voice of God narration by Morgan Freeman makes any piece of media all the more superior. Freeman’s narration is a heavenly listen to and never has exposition been so pleasurable to the ears (if only Morgan Freeman could narrate my life). Freeman is only one-third of the trio of powerhouse performers in Million Dollar Baby. Hillary Swank as Mary Margaret “Maggie” Fitzgerald has a real earnest likeability with her Infectious enthusiasm and down-to-earth manner. The relationship she shares with Frankie is a fascinating insight into what could be described as a surrogate father and daughter. Maggie often speaks of the admiration she holds for her deceased father while Frankie is estranged from his own biological daughter who refuses to speak to him – the two fill a void in their own lives. Frankie’s character arc is the classic, corny dichotomy of a grumpy old man who learns to love but with the strength of the film’s material, it never comes off as feeling cheesy. Concurrently, I would be remised if I didn’t speak of Maggie’s family (God, I hate them so much) – the ungrateful, unsupportive, hillbilly, welfare scroungers. They visit Maggie in the hospital but only in order to have her legally sign away the fortune she earned (and only after they had been there for a week visiting Woody and Mickey). They are cartoonishly evil but it does work on an emotional level as they do get my blood boiling.

Million Dollar Baby is one of the rare instances of a film to feature the Irish language (also known as Gaelic) as Frankie attempts to learn the little-known language throughout the film and gives Maggie her own Gaelic slogan “Mo cuishle”. You don’t get any street cred for being an Anglo-Saxon, but you do for being Irish, although the Fitzgerald dynasty themselves were from Anglo-Norman origins they were described in the Annals of the Four Masters as having become “More Irish than the Irish themselves”. As Scrap says in his narration “Seems there are Irish people everywhere, or people who want to be”.

The final act of Million Dollar Baby, in which Maggie has become paralysed following her injury regarding the stool is the most controversial aspect of the picture. Million Dollar Baby was made during the Terry Shivo controversy and one could look on at the picture as an example of an Oscar bait film trying to capatilizing on the current thing. However, I don’t find its inclusion as part of the film’s story to be contrived or tacked on. Alongside abortion and the death penalty as some of the most difficult moral questions, assisted suicide is a topic of which Million Dollar Baby is ambiguous enough that I wasn’t left with the impression that the film was taking sides. The film does present a condemnation of assisted suicide from a religious point of view in which Father Horvak informs Frankie that “If you do this thing you’ll be lost, you will never find yourself again”. Likewise, the closest the film makes (albeit indirectly) to an argument in favour of Maggie’s life being ended is the monologue given by Scrap in which he speaks of how Maggie got her shot and can leave the world thinking “I think I did alright”. Regardless, watching Maggie in a paralysed state after her life-threatening injury is difficult to watch as she receives bed sores, one of which results in her leg being amputated.

Million Dollar Baby does raise the thought-provoking question of how much quality of life one can still lead when in a condition like that of Maggie? Evidently, for Frankie, it was one not worth living as he turns off her breathing machine and gives Maggie a shot of adrenaline (following Maggie’s own failed suicide attempt through blood loss from biting her tongue). It is left to the viewer’s imagination to picture his subsequent arrest by the police, however, the film does hint that Frankie could have taken his own life as he is seen putting two syringes into his bag beforehand (it’s up to you my good viewer to decide). To go back to Scrap’s words of “I think I did alright”, it does leave me as a viewer with a gratitude to be alive. I know it’s easy to throw around the “M” word, but in this instance, I will use it. Million Dollar Baby is nothing short of a masterpiece and Clint Eastwood’s finest hour as a director.