The Pen Is Mightier Than The Sword

***This Review Contains Spoilers***

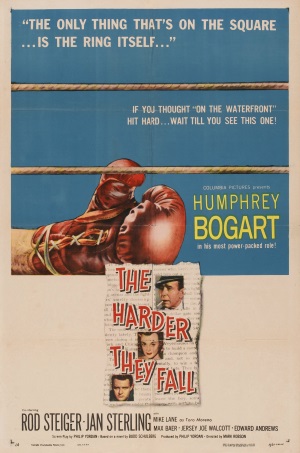

It’s unique to see Humphrey Bogart in a more contemporary, neo-realist 1950’s film in the form of The Harder They Fall. From the Saul Bass-inspired opening credits which help set up the plot (rather than just a series of static title cards) to the punchy music score, I imagine if Bogart lived longer and stared in movies for at least a few more years they would have been aesthetically in a similar vein to The Harder They Fall.

The Harder They Fall deals with corruption and fixing in boxing and how promoters exploit athletes regardless of their health or well being, providing an in-depth look at corruption in boxing as to who pulls the strings and how. The fight scenes themselves don’t suffer from the dilemma of old boxing films having dodgy looking bouts with sped-up footage or obviously fake punches, partially due to the fact that the fights within the film are staged and of poor quality fight tactics. Likewise, the grime and sweatiness of boxing arenas and training gyms never fail as effective subjects to capture on film, especially in black and white. Also, what’s the deal with that bus with the cardboard cutouts attached to it? It’s almost like a character in itself.

More so than any other Bogart film do we see such a striking generational clash with Bogart coming from the old school style of theatrical acting and Rod Steiger from the Marlon Brandon, method school style of acting. However, I’ve always found Bogart to be a very adaptable actor and he is able to seamlessly play of Steiger despite their acting styles being worlds apart. Bogart’s role as washed up columnist, Eddie Willis is one of the most interesting heroic performances of his career which combines Bogart’s trademarks of both world-weary cynicism but also, a sense of righteous morality as he deals with his moral and ethical conscience throughout the film. Eddie can draw up fake publicity for the not so talented, big lug Toro Moreno (Mike Lane), writing articles stating he is the heavyweight champion of South America, undefeated in 39 fights and largely get away with it – that’s the pre-internet world for you (“Nobody reads these west coast papers in the east”).

Eddie may take part in the world of boxing corruption but he never fully believes in what he is doing and tries to make the outfit as unscrupulous as possible. Not to mention he is the only person in the racket who genuinely cares about the gargantuan Toro, whereas the rest of the men couldn’t care less about him. Rod Steiger on the other hand as corrupt sports promoter Nick Benko is an impulsive, brash character who has no moral or ethical conscience – you have to ask does he actually believe in what he is doing is justified in his mind. Steiger chews the scenery throughout the film in a very shouty, loud-mouthed performance which has shades of DeNiro or Pacino coming through.

I had a sense of melancholy during the movie’s closing shots knowing this was the last time Bogart appeared on screen. Bogart was in poor health during the film’s production, suffering from lung cancer (although ironically it doesn’t stop him from lighting up during the movie). In the film’s conclusion, The Harder They Fall celebrates the power of writing as a force to fight wrong and enforce positive social change – proving once again the pen is mightier than the sword, or should I say boxing glove. In the powerful final shot, Eddie begins typing an article on boxing corruption and reformation for the sport, an aspiring sight for any budding non-fiction writers.

“The boxing business must rid itself of the evil influence of racketeers and crooked managers, even if it takes an Act of Congress to do it.”