Am I So Out Of Touch? No, It’s The Students Who Are Wrong

***This Review Contains Spoilers***

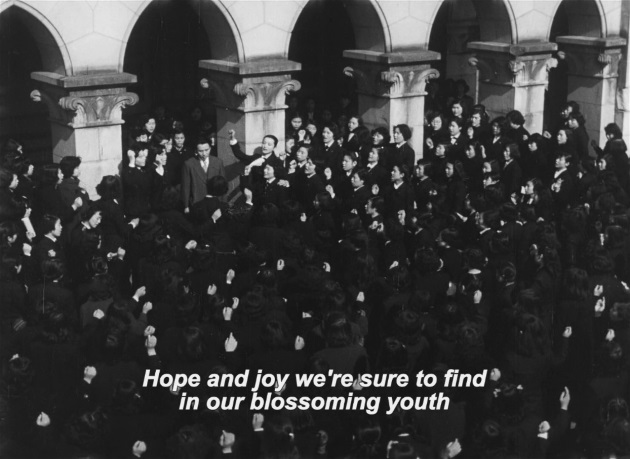

The Garden of Women could have come straight out of Berkeley, California in the 1960s, but no, this is Japan circa 1954 in the fictional Shorin Women’s College, Kyoto. The exact nature of the higher educational establishment in the film is unclear. It has the hallmarks of a boarding school and requires students to wear a uniform but it is not an institution for minors. On the other hand, it would appear the college may be a finishing school however the term is never used in the film. Regardless, following the film’s opening scene of students rallying together following the death of an unspecified character, the film presents a prologue stating; “The students demand academic freedom and human rights. The school wants to maintain its tradition of refinement and personal betterment. But must there be friction between the two?”. So you’re probably wondering how we got into this situation, well for that, we have to go way back…

While it would be fun to declare that Shorin Women’s College is a based and red-pilled intuition that did nuffin wrong, I will offer up the less sexy partial defense of the college against its rebelling students;

-Firstly, the students are attending the college at their own will. The institution itself is not forcing anyone to attend (as evident by a student declaring at one point “Why did I choose such a college?”).

-Secondly, it is established the college is 47 years old. It is a very arrogant attitude to join an institution and then proclaim you will change it from the inside out.

-Thirdly, the college is very front facing about its conservative morals and anti-communist stance, therefore the students should have had expectations of what they were getting into and that an establishment like this is not going to look too favourably upon books on dialectical materialism. To quote Robert Conquest; “any organization not explicitly right-wing sooner or later becomes left-wing”.

-Lastly, there is a genuine lack of stoicism among many of the students, as much of the instigation for the student’s rebellion comes from the petty rule-breaking of student Tomiko Takioka (Keiko Kishi), failing to wear proper uniform and breaking curfew.

So where does fault lie with Shorin Women’s College and in what ways do the students hold legitimate grievances? Well, the college is overly parental with its students who are legally adults, lecturing them on sex, pastimes and their social lives. Especially the college’s matron (Mieko Takamine) whom it can be argued is too involved in the lives of her students. Secondly, the college goes through the mail of the students which is highly unethical and should not be tolerated in a free society. However, the biggest issue with the college in my book is the vicious circle the institution finds itself in from receiving financial support from the family of one of its students by the name of Akiko Hayahiro (Yoshiko Kuga).

Akiko Hayahiro is the most interesting character in the picture and Kuga steals the show with her performance which becomes increasingly sinister as the movie progresses. Akiko openly claims she is a communist however other characters in the story remain doubtful of her claims and see her as a larper. Regardless this champagne socialist comes from a wealthy and connected family who spend summers at a swanky beach. A communist who comes from a privileged background? Why, I am shocked, shocked I tell you! Even the character of Toshika is dismayed at this and can’t wrap her head around it. Due to her family’s connections to the college, Akiko receives establishment protection, as, despite the college’s purported values, she is allowed to do as pleases and receives no pushback from the faculty. As a result, the uprising she helps launch in the film’s third act, the college largely has itself to blame.

Moreover, in contrast to Akkio is Yoshie Izushi. Hideko Takamine should be too old at age 30 to portray an early twenty-something student but actually plays the part convincingly. As Yoshie, Takamine portrays a character who exudes such levels of sadness and despair as she holds Silvia Sydney’s beer. She struggles with her studies, in part from her overbearing father who doesn’t want her to marry the man she loves, but also because she had to work for 3 years after high school in her father’s Kimono shop, has forgotten almost everything and is denied the request to live and study off-campus. Such a request is denied to her by the college’s matron Mayumi Gojō (Mieko Takamine, no relation to the other Takamine), aka The Shrew. The Matron does strike the balance between being strict but friendly with the sense that she does have the student’s best interest at heart. Near the film’s conclusion, it is revealed the matron has a tortured past of her own as she once had a marriage banned by her parents and a child taken away from her. However, I would argue this reveal wasn’t necessary as Mieko Takamine’s performance already gives the character many layers, this added reveal doesn’t contribute to any additional characterization.

I do love a film set in a higher education setting from the crass to the more sophisticated (with any film of this nature, I can’t help but have The Kingsmen’s cover of Louie Louie play in my head.) The filming location for the fictional Shorin College however remains a mystery (unless anyone had info I’m not privy to). That said, the film’s sets have that lived-in quality, reminiscent of a classic English boarding school with various Japanese touches (ground furniture, paper doors etc). These sets are beautifully showcased with the film’s high-contrast cinematography as well as many lengthy, intricate, Mizoguchi-style camera pans (the film even features several striking deep focus shots of Himeji Castle in the city of the same name). One of the most memorable scenes in The Garden Of Women, for both its content and aesthetic beauty, is that of Yoshie and her boyfriend walking and talking about the present as well as their uncertain futures, with the sunlight reflected in the lake behind them as the camera pans really add to the romantic nature of the scene. Yoshie also gives one of the insightful comments in the film in which she describes the two types of women who attend the college. Those who really want to study to begin a career alongside men, and those who want a diploma as part of their dowry, of whom are the majority.

Eventually, the pressure on Yoshie becomes too much and she takes her own life, causing the already brewing student rebellion to go into overdrive as we return the events from the film’s prologue. The students blame the college for Yoshie’s suicide, even though her problems existed before she attended the college. Their use of her as a martyr in their cause is highly dubious as the students themselves alienated Yoshie and drove her to tears at one point when all she wanted to do was study. The Garden Of Women does not end in a pretty manner with everyone blaming each other for Yoshie’s death and the central conflict between students and the college remaining unresolved.

A film which could be tighter in areas, The Garden Of Women is a lengthy but rewarding affair. The middle portion of the film which takes place outside the college during the winter break and deals with a number of ancillary characters could have been left on the cutting room floor, which would have improved the film’s flow. Regardless, The Garden Of Women is a thought-provoking piece of work and not a film of two-dimensional bad guys as brief descriptions of the film might indicate. It is much more nuanced than that and doesn’t frame a narrative portraying one side as villains or clearly in the wrong. 1954 is arguably the apex year of Japanese cinema, seeing the release of Seven Samurai, Godzilla, Sansho The Bailiff, as well as director Keisuke Kinoshita’s other academia-based movie of 1954, Twenty-Four Eyes. The Garden of Women is an underrated gem within a single year’s amazing output.

![The Garden Of Women [女の園/Onna no sono] (1954)](https://satinyourlap.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/1000full-the-garden-of-women-poster.jpg?w=300)

![A Geisha [祇園囃子/Gion bayashi] (1953)](https://satinyourlap.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/800px-gion_bayashi_poster.jpg?w=300)