For several years of my life, I was employed as a cleaner, first in a factory and later in a care home. The latter of which labelled my job as a “Domestic Assistant”, essentially the cleaning equivalent of calling a Garbage Man a “Sanitation Officer”. Regardless, there is zero shame in being a cleaner. As a cleaner, you are providing an invaluable service in keeping the world a tidier and more pristine place.

Being a neat freak myself, I enjoy cleaning; it’s therapeutic, and it’s always satisfying to look over a freshly cleaned room or area. Since then, I have moved on to other things in my life. However, if there is one thing I look back upon my cleaning days with PTSD levels of horror, it’s those dreaded words (in a Northern Irish accent), “Oh gee, sorry lad. I’m walking all over your good clean floor”. Thus, I will provide 4 reasons why apologising to a cleaner for walking over the floorspace that they have cleaned or are in the process of cleaning is not only very annoying (as much as it might be a well-intentioned natural human reflex) but also lacks any basis in logic.

1. It’s Annoying

When an individual says those infamous words or some variation of “sorry for walking over your clean floor”, it is usually said in a confident tone of voice as if the person in question has thought up of a really witty joke and can’t wait to tell their friends. In reality, to the cleaner, this is not a smart and witty piece of self-deprecating humour because they (without exaggeration) hear this multiple times every single day. You may potentially be the 7th person to have said this to the cleaner during the morning shift alone.

2. The Action Itself Doesn’t Actually Cause Any Inconvenience

Walking over a floor which is being cleaned or has just been cleaned doesn’t actually cause any uncleanliness to form. Unless someone is walking over the floor with dirt hanging off their footwear, now that’s different. However, the average sole of a shoe which has just come in after walking on a normal street, will not cause create any such mess.

3. The Apology Is Directed At The Wrong Person

The phrase “your floor” is illogical in itself, as the cleaner doesn’t actually own the floor in question; usually, it will belong to a company. Even if it were the case that walking over the floor caused uncleanliness, then apologising to the cleaner is a futile gesture. Rather, your apology should be directed at the owner of the establishment or if it’s a residential setting (care home, house share, etc), towards the residents.

4. Not Walking Over A Clean Floor Would Cause Mass Disruption

If every motor vehicle on the road were to reduce its speed by 10mph, it would save lives in terms of road accidents. However, as a society, we choose not to do that due to the economic damage and sheer inconvenience that would cause. The same logic applies to walking over a clean floor. Imagine how disruptive it would be if everyone had to wait for a floor to dry before walking over it. “Hey Bill, do you mind giving me a hand with this? Sure, John, in 5 minutes, when the floor between us has dried”.

They often say “the road to hell is often paved with good intentions”; well, in this case, the road to hell is often cleaned with good intentions. Next time to see a hard-working man or woman ensuring the world is a tidier and more pleasant place to inhabit, give them a friendly smile and a “hello”, but for the love of God, do not apologise for walking over “their” clean floor.

![Departures [おくりびと/Okuribito] (2008)](https://satinyourlap.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/mv5bmtuzotcwota2nv5bml5banbnxkftztcwndczmzczmg4040._v1_fmjpg_ux1000_.jpg?w=300)

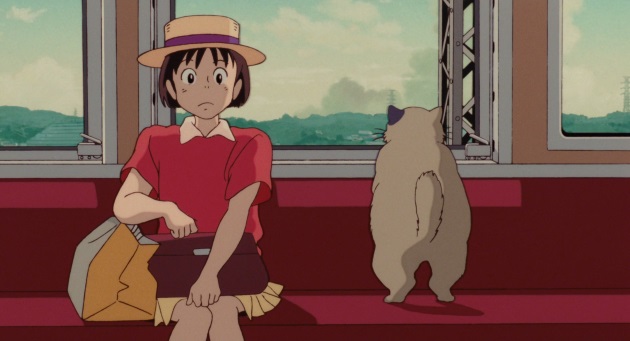

![Whisper Of The Heart [耳をすませば/Mimi o Sumaseba] (1995)](https://satinyourlap.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/whisper-of-the-heart-md-web1.jpg?w=300)