Wait A Minute, There Were No Scattered Clouds In Scattered Clouds!

***This Review Contains Spoilers***

The plot synopsis of Scattered Clouds (aka Two In The Shadow or its original Japanese title Midaregumo) sounded fascinating and had me asking myself, how does such a scenario play out in a believable and non-contrived manner? A man falls in love with the widow of a man whom he killed in a car accident and eventually, she falls in love with him in return. Sounds like the type of intriguing fodder for a daytime talk show, I can just imagine the Jerry Springer-style title – “I’m In Love With The Man Who Killed My Husband”. However, the closest counterpart to Scattered Clouds is Lloyd C Douglas’ 1929 novel Magnificent Obsession (itself later adapted into a 1954 film by Douglas Sirk).

There is a little-known acronym for a person who is responsible for the accidental death or injury of another known as a CADI (Caused Accidental Death Or Injury). The term has no official recognition but to date is the closest term in existence for such an individual. Mishima Shiro (Yūzō Kayama) accidentally kills another man by the name of Hiroshi Eda (Yoshio Tsuchiya) in a car accident, leaving his wife Yumiko (Yōko Aizawa) widowed. The accident itself is not portrayed on screen nor does it have any build-up, it is just announced out of nowhere 8 minutes into the film, making its impact all the more shocking and reflective of reality. Mishima is later found in court to be not guilty of negligence (lost control of his vehicle due to a burst tire) and the film shows the negative toll it takes on the CADI with his company forcing him to relocate which in turn ends his current relationship and leads to depression. At the same time, his guilt and compassion result in him paying money in monthly installments to the newly widowed Yumiko even though he has no legal obligation. That said, Mishima doesn’t have the wisest of intentions when he chooses to actually attend the funeral of the man he accidentally killed (even if it is to pay his respects), and easily gives away that he is the man responsible (keeping in mind he hasn’t been acquitted at this point). Evidently, his unwise decision-making extends to later in the film with his cringe-worthy attempt to woo Yumiko with a Tommy Wiseau-level line (“You were so cute, like a child, when I surprised you. Actually, you were amazingly sexy too”).

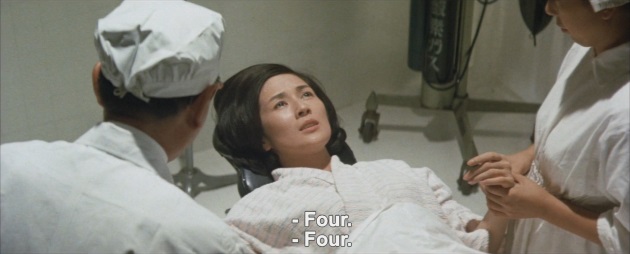

The tragedy of Yumiko Eda on-the-other-hand actually reminded me of George Bailey from It’s A Wonderful Life, a character whom the world is their oyster with the prospect of travelling and seeing the world, only to have it taken away and instead find themselves stuck living in a dead-end town. Before his untimely death, Yumiko and Hiroshi were set to move to Washington D.C. after he got the job as an ambassador for the company he works for. This plight of a woman who was dependent on her late husband also results in the disappearance of her unborn baby, only in the womb for three months at the time of her husband’s accident. Shortly afterwards she goes to a hospital in which all that is shown is a doctor telling her to count to seven, after which there is no mention of the baby: miscarriage, abortion, stillborn? Abortion was and still is legal in Japan if the mother meets an economic threshold of poor living conditions. Prior to this scene in the hospital, Yumiko is forced to endure dehumanizing bureaucracy following her husband’s death (not to mention there are even discussions of Hiroshi’s replacement at his own funeral) in which she is told “No additional postnatal allowance will be paid for a pregnancy under five months” – make of that that what you will.

The plot in Scattered Clouds does have some reliance on coincidence bringing the characters of Yumiko and Mishima together. In particular, Mishima is relocated by his company to the town in which Yumiko grew up and decides to move back following her husband’s death (that being Aomori in the prefecture of the same name) but does so without the contrivance getting in the way. Scattered Clouds does a remarkable job of conveying the naturalistic evolution of their relationship, going from Yumiko’s inability to even look at Mishima to the pair eventually falling in love. Much has to be commended for the chemistry of the two actors in making this transition believable but the real turning point in the relationship is when Mishima finally challenges Yumiko on the way she treats him despite all the amends he has tried to make, only then does she herself begin to feel a sense of guilt. I believe the other aspect which aids the believability of this unorthodox romance is the Florence Nightingale syndrome from when Yumiko spends the night caring for Mishima after he catches a fever. Scattered Clouds can serve as a companion piece to Mikio Naruse’s earlier film Yearning (Midareru), with both films featuring Yūzō Kayama in a highly unlikely will they/won’t they relationship.

Scattered Clouds also has an odd distinction of featuring quite a few “put-downs” of various eastern hemisphere cities. Aomori, where much of the picture takes place (not to mention filmed) is described as having people who are blunt and unfriendly as evidenced by the waitress at the café, serving coffee with no care. Then the city of Lahore in western Pakistan (from which Mishima is to be transferred) is described as an “awful place” as well as the movie claiming it is the birthplace of cholera. I can’t find any evidence this is the case so was this a misconception in Japan at the time (I suppose it doesn’t help when your city sounds like the name of a French prostitute)? To wrap things off, whether justly or unjustly, the film describes Dhaka, Laos, Saigon and Karachi as places no one wants to go.

Scattered Clouds was Mikio Naruse’s final film of a 37-year career and can go down as one of the finest directorial finales. Scattered Clouds is only Naruse’s 3rd film in colour and only work in the post-black & white era and while the picture does have a more cotemporaneous feel than had it been made a few years earlier, there is still a dreamlike quality present. I just have to enquire as to what is the meaning of the film’s title as nowhere in Scattered Clouds are scattered clouds present. Well, the original Japanese title Midaregumo actually translates to Turbulent Clouds (which are present within the film during a key scene in which Mishima comes down with a fever). I guess Scattered Clouds has a more romantic ring evoking classic melodrama.

![Scattered Clouds [Two in the Shadow/乱れ雲/Midaregumo] (1967)](https://satinyourlap.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/mv5bzdhlztjmmgutzwrjmi00mgu0lwfhzdytywm3mzvjzdniytuxxkeyxkfqcgdeqxvymjg1njgwmzg40._v1_fmjpg_ux1000_.jpg?w=300)

![When A Woman Ascends The Stairs [女が階段を上る時/Onna ga Kaidan o Agaru Toki] (1960)](https://satinyourlap.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/mv5bztk0ztzjy2mtytdhzi00owqxlwjkmwutmzk4ztnkotbimthhxkeyxkfqcgdeqxvynzc5mja3oa4040._v1_fmjpg_ux1000_.jpg?w=300)