The Cinema Has No Boundary, It Is A Ribbon Of Dream

***This Review Contains Spoilers***

Giuseppe Tornatore’s Cinema Paradiso is the ultimate movie lovers’ movie. A film which perfectly captures the obsessive and domineering power cinema has over its dedicated fans and their lives. In the manner of how the picture’s protagonist Toto becomes enchanted and engulfed by the movies, Cinema Paradiso is a movie which succeeds in doing just that. Cinema Paradiso takes the viewer back to a time when the movie theatre was at the heart of a community, where people would even have sex in the middle of a crowded theatre and teenage boys would engage in acts of self-pleasure to what was on screen (must be a European thing), or alternatively, many would just go to enjoy a nap. Cinema Paradiso is my favourite Italian film but also my favourite film not in the English language, and what a rich experience it is. Even the Italian people’s over-the-top, histrionic nature is hugely entertaining – now that’s a good-a pizza pie! The music, scenery and vibrant architecture of the village of Giancaldo on the island of Sicily immediately draw me in with the stone buildings, fountains, cobblestone streets and wide open squares free of automobiles. This contrasts with the film’s latter scenes set in the modern day, where modernity has replaced a world in which the influence on Ancient Rome still lingered and instead with something more superficial and ugly.

Cinema Paradiso follows the relationship between the child Salvatore “Toto” Di Vita and his Freudian father figure Alfredo (Philippe Noiret), a projectionist at the local cinema. Alfredo himself is very much a mythical character; he has no back-story or even a surname (he does have a wife yet we only see her briefly), yet he succeeds in being one of the most unforgettable characters in film history. He is a man who appears to have never made much for himself in life yet to Toto, this cinema projectionist is the most fascinating man in the world – the archetype of a loser with a heart of gold. This is one aspect of the story which really punches one in the gut; Alfredo prevents Toto from going down the same road as he did but at the cost of moving to Rome and never seeing him again of his family again as the village would have a destructive influence on the artistic development of someone like Toto. The job of a projectionist is no path for a young man of whom the world is his oyster. Ultimately, this works, as we learn from the opening and closing of the theatrical cut of Cinema Paradiso (more on the director’s cut later) that Toto holds a job of some esteem in the film industry (possibly a director although it’s not made clear) and lives in a not too shabby Rome apartment, but only by the way the of great sacrifice imposed by Alfredo. The man may not have had much education, but it’s clear he had the wisdom of age.

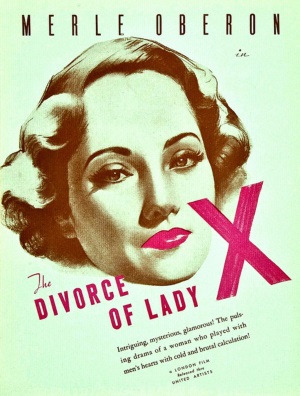

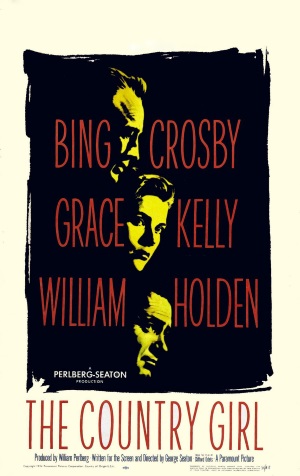

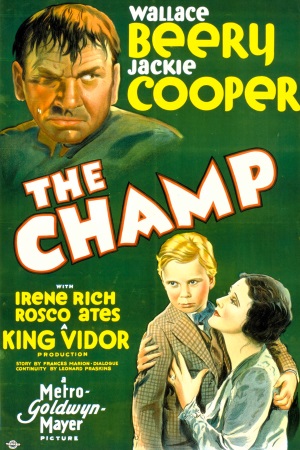

The question has to be asked, is Cinema Paradiso the most tear-inducing film ever made? I recommend wearing a life jacket while watching this movie or you will drown in your own waterworks. This is one of few films that give me teary-eyed goosebumps even thinking about it or by listening to the music score by Ennio Morricone. The entire score is one of few I can listen to in its entirety, full of compositions of pure tranquillity to reminisce on days gone by. I hate to imagine how much of a nihilist one would have to be not moved by the scene in which Alfredo makes a projected image travel along the walls of the projection room and into the town square accompanied by the booming music score. Alternatively, take the scene in which or a lonely teenage Toto walks through the streets of Giancaldo just as New Years rolls in after being rejected by his love Elena. I also personally find it hard to retain a straight face at the utter soul-crushing scene near the film’s end as the adult Toto walks through the abandoned interior of the Paradiso on the day before it is set to be demolished to make way for a car park. However, it is the final scene in which Cinema Paradiso really does save the best for last, a conclusion which is movie magic of the highest magnitude. Aside from being a tribute to the 20th century’s greatest art form, Cinema Paradiso is full of emotions of nostalgia, youth, love and the losses we have to deal with during our lives. Like the stamp of any truly great film, Cinema Paradiso is a movie which you don’t want to end and the streamlined version of Cinema Paradiso is Cinema Perfecto. Oh yes, there’s more, with the director’s cut of Cinema Paradiso which adds not only so much more additional material to the film, but so much more depth and complexity to its characters which bares discussion.

For the original Italian release or director’s cut, Cinema Paradiso had a run time of 173 minutes and for the international release, it was cut to 124 minutes. The biggest difference with the director’s cut is the far greater examination of the relationship between Toto and Elena, transforming what is a subplot in the cut version into one of the main focuses of the story, especially during the picture’s third act. In the theatrical cut, there is only a hint that Elena’s middle-class parents object to her relationship with Toto but in this longer version, this objection is on full display. However more significantly, we learn in a crucial flashback scene, that it is Alfredo himself who worked to end this young love, viewing Elena as another obstacle to Toto’s artistic development. Toto and Elena’s contemporary reunion scene is an incredibly lengthy and talkly affair, outlasting by great magnitude any other scene in the film but its emotional payoff is satisfying and in the end, both characters come to accept that Alfredo was justified in his actions.

In the theatrical cut of Cinema Paradiso it’s merely hinted that Toto has become a film director but in this version, it that not only the case, but he is also famous enough that he is recognised by fans in a bar. In regards to other new scenes, that in which the film acknowledges the rise of television by having a game show projected in the Paradiso via a teleprojector much to Alfredo dismal is a nice addition, foreshadowing the eventual demise of the local cinema. Other scenes however I did find unnecessary such as adult Toto’s encounter with the street punks in Rome to Toto’s friend Boccia getting some action in the countryside. Although the one scene I really didn’t need to see was Toto losing his virginity to a cougar in an empty paradiso and just before meeting his later love, taking away from the character’s innocence. I have to say I greatly prefer the shorter, more streamlined version of the Cinema Paradiso. The additional material of the director’s cut greatly affects the film’s pace and takes away much of the mystery posed by the shorter cut. Likewise, the majority of the additional scenes are set in the modern day and stylistically do feel very distant from those set in the Sicilian village of the ’40s and ’50s, thus at times, it does feel like I’m watching an entirely different film altogether. That said, even though it is a flawed version of the film, I am glad this cut exists as it does contain its own merits turning the film into something of an epic and reminding me of another film with an Ennio Morricone score with similar coming-of-age themes, Once Upon A Time In America.