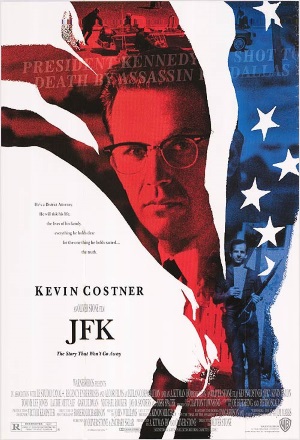

JFK, Blown Away, What Else Do I Have To Say?

I’m aware in modern times conspiracy theories have become detrimental in discovering the actual truth (largely thanks to the internet) but I can’t deny that I just love this sort of stuff. JFK requires your utmost attention and at a runtime of three hours, it feels like the movie leaves no stone upturned (pardon the pun) in its examination and deconstruction of the Kennedy assassination. Admittedly the first time I watched JFK I didn’t understand much of what is discussed in the film. It’s a lot to digest in a single viewing but there are more intriguing theories here than an entire season of Ancient Aliens (minus the bad haircuts and awkward line delivery); but I can happily watch JFK multiple times to further understand it and eat up every single word of dialogue. I doubt we will ever need another film made about the Kennedy assassination; what highly talented filmmaker could be more passionate about the subject matter? I also highly recommend watching the director’s cut for even more conspiracy goodness to evoke the paranoia in you.

JFK is one of those movies which makes you most appreciate the art of editing, incorporating many layers of time and reels of stock footage; no scene during the movie’s three hours is edited in a standard fashion. The editing help make the film’s exposition exciting; a character may be describing an event as the scene cuts to just that in an obscured or dreamlike manner. The Mr. X sequence with Donald Sutherland is a perfect example of how to pull of engrossing exposition; plus is there a more classic cold war, spy movie type scene than meeting a suited man in the park to receive classified information. Likewise, John Williams’ theme for JFK evokes my inner patriotic American, even if I’m not American. The militaristic and at other times conspiratorial nature of the score helps make the movie as compelling as it is. The black & white scenes such as those featuring the military feel reminiscent of Seven Days In May with shades throughout of the John Frankenheimer style. I’m sure Stone must have also taken some pointers from the first movie about the Kennedy assassination, 1973’s Executive Action.

JFK continues the tradition of films such as The Longest Day in which a large ensemble cast of familiar faces and great screen presences to help guide us through the story. It’s amazing seeing different generations of actors doing some of the best work their careers and utilizing their screen personas to full effect even if many of them are only on screen for short spaces of time. Some of the figures in the story strike me as too bizarre to have been real-life people, especially David Ferrie and Claw Shaw.

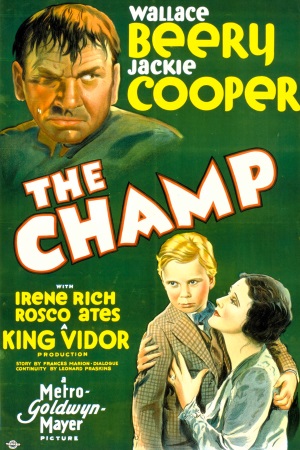

I’ve always been in defense of Kevin Costner against criticisms of being a dull actor. Granted his career did go downhill in mid 90’s and has never fully recovered but in his heyday of the late 1980’s/early 90’s he was such a hot streak of films. Casting him in the role of Jim Garrison couldn’t be more perfect as Costner is much like a modern-day classic movie actor in the vein of everymen like James Stewart, Henry Fonda or Gary Cooper. He’s been most commonly compared to Cooper (the courtroom section of the film is reminiscent of Cooper’s role in The Fountainhead) although with his southern demeanor I would compare him to being a modern-day Henry Fonda. I would defy anyone to call Costner a bad actor after watching the film’s courtroom scene. Talking almost non-stop for 40 minutes and never losing my attention while exuding a stern, emotional and towards the end of the speech, a fragile voice; with his final conclusion bringing a tear to my eye.

I find Jim Garrison’s family life interesting itself, mostly from the relationship with his wife. What does he see in her? She does not support his endeavors, despite his noble cause and unlike her husband, she is susceptible to believing what the media tells her. Here is a man who spends the movie questioning and fighting the system yet has a wife with a conformist personality. I can’t say for certain what they were like in real life but the in film I grew to dislike her character.

JFK draws no conclusions, it doesn’t prove who assassinated Kennedy and allows the viewer to make up their own mind. Stone may be often criticized for his use of a dramatist’s license but as I say with many films based on historical events; this can make for a more compelling story. Even if there are untruths present, the film can act as a gateway to wanting to discover the real story. The movie did leave me a feeling of (good) anger and is one of the films I can credit with helping to influence the way I think.

“Dedicated to the young in whose the spirit the search for truth marches on.”