I Love Democracy…

***This Review Contains Spoilers***

I do love the efficiency and streamlined nature of pre-code films. Within two minutes, the opening credits roll, followed by a montage of stock footage, and the story of Gabriel Over The White House is underway (unlike films today with a parade of 10 studio logos and a title screen that doesn’t appear until 40 minutes in).

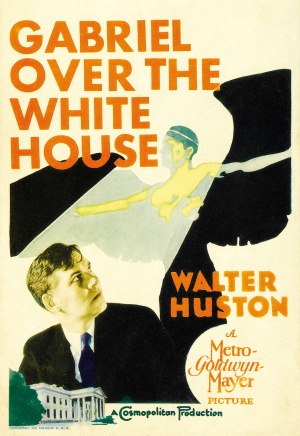

The newly elected President of the United States, Judson Hammond (Walter Huston), is sworn into office, yet behind closed doors, he and his inner circle treat the presidency as a joke. They engage in smarmy chatter and look down upon the populace (“When I think of all the promises I made to the people to get elected…by the time they realise you’re not going to keep them, your term will be over”). Hammond even takes the pen that Lincoln freed the slaves with and remarks, “Well, here it goes for Puerto Rican garbage”. To play up this disregard to an even greater degree, in a very unusual scene featuring a rare use of overlapping dialogue, the President and his nephew play a treasure hunt game in the Oval Office while the radio plays an activist speech. The audio from the dialogue between the President and his nephew becomes drawn out by that of the radio, as Hammond does not have a care in the world for what’s happening in the country. The only loyalty displayed by Hammond is towards what is simply referred to as “The Party” (“The party has a plan, I am just a member of the party”). Walter Huston has the look you would expect from a president from the early 20th century (not too dissimilar looking to Warren G. Harding or a clean-shaven William Howard Taft), while his sheer gravitas not only makes the hairs on your skin stand up, but he also prevents Hammond from coming off as just a caricature. Interestingly, however, he is a President without a First Lady, which would make him and James Buchanan the only unmarried presidents.

Following a racing accident, Hammond goes into a coma. However, upon his reawakening, Hammond is no longer the man he once was; rather, a populist figure is born. “God might have sent the angel Gabriel to do for Jud Hammond what he did for Daniel”, states the President’s secretary, Pendie Molloy (Karen Morley), as the film makes no secret of indicating that Hammond will be enacting the will of God himself. Many scenes from this point onwards have a softer, more dreamlike look, with a higher contrast between black and white. In one moment shortly after Hudson’s awakening, he stares up in awe at a bright heavenly light shining upon his face, or as Pendie describes it, “the presence of a third being in the room”. Many a beautiful shot populates the film, from the dramatic zoom shot on Hammond (even if it does go in and out of focus) to some stunning set design with the art deco set of the film’s court martial scene.

The new Judson Hammond wastes no time getting things done with his newfound heavenly, populist political will. Right off the bat, he stops calling his staff nicknames and stands up to the members of his own party.

“Now, be careful. I might resign on you.”

“Your resignation is accepted.”

“Oh, well now, wait a minute, Jud, I was only suggesting…”

Hammond asks Congress to declare a state of national emergency to adjourn itself until normal conditions are restored, and during this period, he will assume full responsibility for the government. With the country under martial law, Hammond proceeds to tackle the issues of unemployment, mob rule, forcing over nations to pay their debts the US and by the film’s climax, literally enshrining world peace into a document signed by most nations in the world. Upon lending his own signature to the document, Hammond himself collapses and quickly passes away, lending further credence that he is enacting the will of God.

The subplot of Hammond’s efforts to eliminate the mob is particularly interesting. He praises gangster Nick Diamond (of course, he has a scar on his face) directly for “getting rid of most of his own kind”, relating to the theory in criminology that allowing one single crime syndicate to operate results in an overall reduction of crime. Hammond proceeds to create a federal police force to eliminate the mob, leading to two of the oddest scenes in the film, the first in which the mob attempts to assassinate Hammond on the grounds of The White House itself (was this more plausible in 1933?). The latter is a sequence which I can best describe as resembling the climax of every episode of Takeshi’s Castle. Following the arrest of Nick Diamond and his men, they are executed by way of an old school firing shot with the Statue of Liberty in the background (I’ll let you decide what is the intended symbolism, if any, of such a shot).

Is there a name for this kind of populist wish-fulfilment picture? The film which has the most striking similarities to Gabriel Over The White House is Ivan Reitman’s Dave (1993), in which an ineffective, uncaring president is replaced by a populist doppelganger who gets things done. Likewise, multiple sources online speak of an alternative European cut with 17 extra minutes, although such a cut has never been released on home video. Much is made of the fact that film was financed by media conglomerate William Randolph Hearst, although regardless of the agenda those behind the production may or may not have had (although it is worth noting that director Gregory LaCava would go on to direct the anti-New Deal May Man Godfrey in 1936), Gabriel Over The White House, whether by design or not, presents one central dilemma; should a nation be led by one all-powerful leader who can get things done, or have a system of checks and balances, which may be slow and inefficient? When watching Gabriel Over The White House, it’s easy to feel seduced by the temptation of having an all-powerful leader, a benevolent dictator, a king. Or once a crisis has abated, can we ever trust that a leader will lay down the powers given to him? History would say no, but Gabriel Over The White House allows the viewer to indulge in such a fantasy.