Crossing The Rubicon

***This Review Contains Spoilers***

What would possess someone to willingly want to cross the Korean Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) from the safety, prosperity and freedom in the south to the communist, oppressive, hermit kingdom in the north? One such scene in Park Chan-wook’s Joint Security Area (JSA) shows the baseball cap of a tourist being blown off their head in the wind and into the northern side of the JSA (a portion within the wider DMZ), to which they naturally don’t even think about crossing that borderline to go and get it back. In the 21st century, the DMZ is the last remaining piece of the Iron Curtain, an international Rubicon, a seeming point of no return, a barrier one would never imagine wanting to cross from the southern side. Despite being set at one of the most volatile places on Earth, the story of Joint Security Area is localised and condensed to the relationship between a group of soldiers and the investigator sent to uncover the truth of their border crossing exploits.

Major Sophie Jean (Lee Young-ae) of the Neutral Nations Supervisory Commission, the Swiss investigator of Korean descent, is tasked with solving the whodunnit in a “perfectly neutral” manner alongside her Swedish partner (Herbert Ulrich). As the audience surrogate, she is soon provoked by southern authorities with such comments as “There are two types of people in this world, commie bastards and the commie bastard’s enemies”. The North Korean authorities, on the other hand, present her with a series of staged theatrics, including an apparent grieving North Korean family, to dealing with a deposition made and signed by a man in a coma. The first act of JSA follows the Rashomon model, in which a series of contradictory stories are presented. This act of the film also plays out as a procedural in classic CSI-like style with the man-woman duo interviewing witnesses and presenting their forensic findings to each other (with the film not holding back any punches with some very graphic gunshot wounds), with Young-ae bringing a feminine presence to an otherwise male-centric movie. The English present in the film does sound very unnatural, although one could argue this would be the case since none of the characters are native speakers of the language.

The middle portion of JSA pivots to a lengthy flashback, as two South Korean soldiers (Lee Byung-hun and Kim Tae-woo) come to befriend several soldiers from the North and start crossing the border every night simply to hang out with them. The bromance they share becomes endearing as they share southern contraband, including pop music tapes, cookies and Choco Pies, while also engaging in male bonding behaviour: looking at nudie mags, cracking jokes, giving playful jabs at each other and at one point, giving a fart as a present. There is still a real cinematic nature to these intimate moments, such as the use of two 360-degree shots during conversation, with Song Kang-ho delivering the standout performance among the soldiers as the North Korean Sgt. Oh Kyeong-pil, the domineering and alpha personality of the group. Joint Security Area was filmed on a mass recreation of the DMZ, and the sets never feel inauthentic and look indistinguishable from the real thing. I recommend watching the making-of documentary for JSA (included in the Arrow Blu-ray release) in which one of the film’s costume designers states that just a few years prior to the film’s production, he may have been breaking South Korean law by recreating North Korean military uniforms.

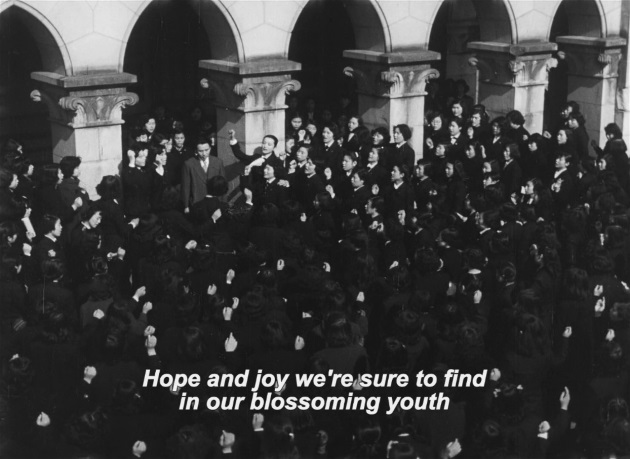

The partition of Korea is the division of a single ethnic group; thus, there is an understanding by many in South Korea that northerners are still their fellow Koreans. This can be seen symbolised by the scene in which the saliva from both a northern and southern soldier is mixed together at the borderline, as well as a prominent shot of the full moon as a soldier throws a package across to the north. In literature and K-dramas, the moon often evokes nostalgia or longing, especially for someone far away. This shared humanity across the border brings to mind historical events such as the football game during the Christmas Day truce in World War I. However, within the flashback of JSA, there is still an underlying suspicion that the northern soldiers are just trying to get the southern soldiers to defect, with a dose of Treasure of the Sierra Madre-style tension. If there is a main recurring theme in Joint Security Area, it is that of façades. Major Jean comes to learn that the real purpose of the Neutral Nations Supervisory Commission is to bury the truth on behalf of both sides, that neutrality is simply a façade. From fake grieving families, fake depositions, questionable friendships and apparent loyalty citizens claim that they hold to regimes, to even Jean herself removing her own father from a family photograph.

With the Korean DMZ being one of the final remnants of the Cold War, which still exists in the 21st century, Joint Security Area has a real old-school vibe (“Rice is communism”, proclaims an archaic billboard on the northern side of the divide). This sense of historical statis is just one of many reasons as to why of the 200-odd nations which inhabit this planet, none are quite so fascinating as The Democratic People’s Republic Of Korea (better known as North Korea). I am a North Korea obsessive (a North Koreaboo if you will) and will consume any bit of media which will increase my knowledge of NK lore. Needless to say, in April 2025, I fulfilled my dream of almost entering this hermit kingdom by visiting The Demilitarized Zone and getting (at closest) 140 metres from the Korean border. Unfortunately, I couldn’t visit the Joint Security Area itself, but could still bring some pieces of the JSA and wider DMZ back with me.

![Joint Security Area [공동경비구역 JSA] (2000)](https://satinyourlap.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/mv5bmti1nda4ntmyn15bml5banbnxkftztywnta2odc5._v1_fmjpg_ux1000_.jpg?w=300)

![Departures [おくりびと/Okuribito] (2008)](https://satinyourlap.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/mv5bmtuzotcwota2nv5bml5banbnxkftztcwndczmzczmg4040._v1_fmjpg_ux1000_.jpg?w=300)

![The Bad Sleep Well [The Worse The Villian, The Better They Sleep/悪い奴ほどよく眠る/Warui Yatsu Hodo Yoku Nemuru/] (1960)](https://satinyourlap.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/poster-resize.jpg?w=300)

![Supermarket Woman [スーパーの女/ Sūpā no onna] (1996)](https://satinyourlap.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/mv5by2e5nddkyjutogu3mi00yjzilwjlnjcty2i1ntc5y2qwmzk1xkeyxkfqcgdeqxvymtcymdgxnq4040._v1_.jpg?w=300)

![The Garden Of Women [女の園/Onna no sono] (1954)](https://satinyourlap.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/1000full-the-garden-of-women-poster.jpg?w=300)

![The Silent Duel [The Quiet Duel/静かなる決闘/Shizukanaru kettô] (1949)](https://satinyourlap.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/1200px-shizukanaru_ketto_poster-1.jpg?w=300)

![A Geisha [祇園囃子/Gion bayashi] (1953)](https://satinyourlap.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/800px-gion_bayashi_poster.jpg?w=300)