Look At Me, Drunken One Night Stand. I Mean She Is My Wife

***This Review Contains Spoilers***

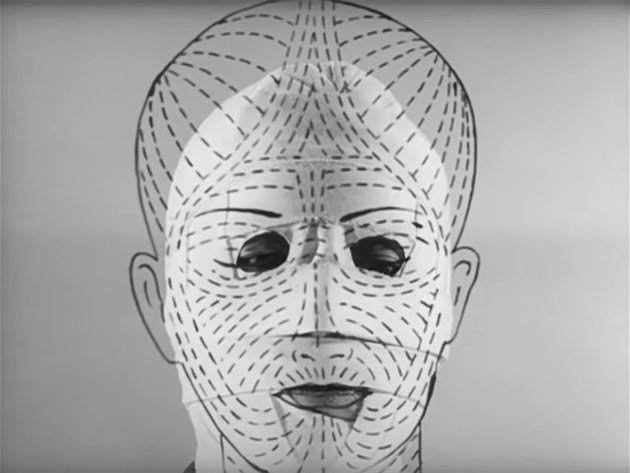

The Face Of Another is an imperfect but intriguing viewing experience from the ever-fascinating face-swap genre. I would call The Face Of Another a unique film but the only thing preventing me from doing so is a similarly themed film (and one released the same year nonetheless) in the form of John Frankenheimer’s Seconds. Both films involve a man in a loveless marriage who goes behind his wife’s back to get both a new face and new identity with the two films being full of avant-garde and neo-realist imagery. Both films have major differences between them too but hold enough similarities to make the pair a great double-feature. The visuals present in The Face Of Another stick with the viewer long after watching, even right from the opening scene which features an x-ray of a skull delivering exposition, while the black & white, high contrast cinematography beautifully captures a documentary-like look at mid-1960’s urban Japan (even Japan wasn’t immune to those dodgy looking 60’s tower block apartments).

We only receive a vague description of how engineer Mr. Okuyama (Tatsuya Nakadai) came to have a disfigured face. It appears to have be an industrial accident as in his own words as he was acting carelessly when inspecting a new factory owned by the company he works for (“We should have used liquid air. But we ran out… we used liquid oxygen instead. I thought it was liquid air”). Mrs. Okuyama (Machiko Kyo) is the wife who has fallen out of love with her disfigured husband – it’s never stated but it’s obvious as she can’t bear to look at his face with the bandages removed. He is no longer the husband she once knew, he is now a skin suit of a husband. The Face Of Another explores how a transformed physical appearance might impact one’s inner personality. It’s not indicated much his disfigurement has changed Mr. Okuyama’s personality or was he always rather unpleasant, neurotic and borderline psycho? Just observe the manner he berates a secretary for not asking who he is when walking into the office. Furthermore, Mr. Okuyama lives in a westernized house with no traditional Japanese ground furniture and is littered with trendy 60’s decor yet there still remain a few traditional Japanese ornaments in the home – showing a modern couple who are caught between tradition and what is seen as modern and hip.

The Face Of Another contains a B-movie story presented within a sophisticated, art-house style. The film is in the mould of the Universal Monsters tradition with the plot’s similar themes to Frankenstein and Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde. Correspondingly, when Mr. Okuyama wears his bandages and fedora he bears more than a striking resemblance to the Phantom of the Opera and Claude Raines’ The Invisible Man (Okuyama later comes to think his newfound face makes him invincible). Throughout the course of the picture, Okuyama visits Dr. Hira (Mikijiro Hira), who is able to offer Okuyama a face transplant in which the facial mask is from that of a donor (a concept which was science-fiction in 1966 but has become a reality today with French woman Isabelle Dinoire receiving the world’s first face transplant in 2005). Just how much of Dr. Hira’s technique creating a face mould which can be taken on and off another’s face still remains science-fiction is a question I am unable to answer. The Cronenbergian figure of Dr. Hira is a more down to Earth mad scientist (if that’s not an oxymoron). He has a slight, subtle twinge of madness to him, with the interactions shared between doctor and patient being my favourite part of the film. He is a medical doctor yet also a plastic surgeon at the same time complete with several nurse assistants within his dreamlike and surreal clinic, which itself is really something to behold. It is a blank space with no observable windows or doors in which the background changes upon every visit and is littered with transparent panels and prosthetic pieces hanging around like works of modern art.

One of the film’s most interesting dialogue exchanges takes place between husband and wife as they have a discussion about the covering of one’s face. They speak of how during Japan’s Genji era it was considered virtuous to conceal one’s face as well this continuing to be the case for women in Islamic countries. There is an accidental modern relevance to this conversation as following the Covid-19 pandemic, the covering of one’s face in the west has become seen as a virtuous act in the eyes of some. Okuyama chooses to use his new appearance to seduce his own wife (unbeknownst to her that the man is her husband), and there is a preserve intrigue that comes from watching this play out. The seduction proves successful however afterwards she claims to have known it was him all along. Did she really know it was him? Would the presence of body markings have given it away?

The Face Of Another also contains a subplot unconnected to the main plot about a young woman whose face is beautiful on one side but disfigured on the other. She is shunned by others and has never been treated like a lady by men other than her older brother (her introductory scene even features an extra whom I swear to God looks like the Japanese half brother of one of The Beatles). Her brother is the only man who understands her pain and solitude and even kisses the disfigured part of her face, leading to an incestuous relationship between the two. Her story acts as a doppelganger to the main plot although I feel it is the weaker and less interesting aspect of the film. The Face Of Another does move at a slow pace and like any art-house film, said elements can test the viewer’s patience but ultimately the patient viewer is rewarded in the end.

During one scene with the disfigured girl, she is walking through a mental asylum housing Japanese war veterans, of which she volunteers her time, all while non-diegetic Hitler chants play in the background. Likewise, throughout the film, Mr. Okuyama and Dr. Hira visit a traditional Munich-style German bar complete with traditional German music. Is the film trying to make comment on Japanese war crimes and the country’s coalition with Nazi Germany? Along with the film hinting the disfigured girl may have received her scars from radiation poising from the bombing of Nagasaki, the spectre of World War II looms over The Face Of Another. Although the pink elephant in the room for anyone familiar with Japan’s involvement in World War II is the clear parallels between the film’s theme of medical experiments and the Japanese war crimes including the experimentation of humans at Unit 731.

![The Face Of Another [他人の顔/Tanin no Kao] (1966)](https://satinyourlap.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/the-face-of-another-md-web.jpg?w=300)

![Red Beard [赤ひげ/Akahige] (1965)](https://satinyourlap.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/mv5bndu5zje1owutzjcxns00njazlthhztqtowy0mdc3ndq1yte2xkeyxkfqcgdeqxvymtiynzy1nzm40._v1_.jpg?w=300)

![The Flavor Of Green Tea Over Rice [お茶漬の味/Ochazuke no aji] (1952)](https://satinyourlap.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/tumblr_55d9d5ea1718af9e3f52902835e75b96_3ba42881_1280.jpg?w=300)

![Floating Weeds [浮草/Ukikusa] (1959)](https://satinyourlap.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/floating_weeds-149228130-large.jpg?w=300)

![Drunken Angel [醉いどれ天使/Yoidore Tenshi] (1948)](https://satinyourlap.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/yoidore_tenshi_poster.jpg?w=300)

![The Yakuza [ザ・ヤクザ/Za Yakuza] (1974)](https://satinyourlap.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/maxresdefault.jpg?w=300)