Bringing Home The Bacon

***This Review Contains Spoilers***

Combining elements from Casablanca, Only Angels Have Wings and A Matter Of Life And Death, Porco Rosso is Studio Ghibli’s romantic, swashbuckling cocktail. Porco Rosso (Italian for Red Pig), real name, Marco Pagot is an ex-Italian World War I fighter pilot turned bounty hunter in the Adriatic Sea. Porco is a Bogartian figure with his cool detachment, political apathy and romantic distance, but his most significant character trait is that derived from his physical appearance. Porco has had a curse put upon him turning him into, well, an anthropomorphic pig. Why is the film’s protagonist a pig? The two most apparent interpretations being firstly a reference to the saying “when pigs fly” and the cultural perception in the west (as well as in faiths such as Judaism and Islam) of pigs being dirty animals (keeping in mind the film is set in a western country). A common reading is that Porco put the spell upon himself out of survivor’s guilt when the rest of his comrades died in battle. He views himself as swine – self-loathing and unworthy of living. It’s only through the validation and the friendship he shares with the character of Fio that comes to cure him of this affliction. How someone possesses the supernatural ability to turn into an anthropomorphic animal is never explained nor does anyone in this world question why there is a walking-talking hog existing among humans. Still, the film has enough going for it to overcome this suspension of disbelief (Porco is even a hit with the ladies despite his appearance so I guess looks aren’t everything). The film’s ending indicates the curse may have been lifted but ultimately leaves the question unanswered.

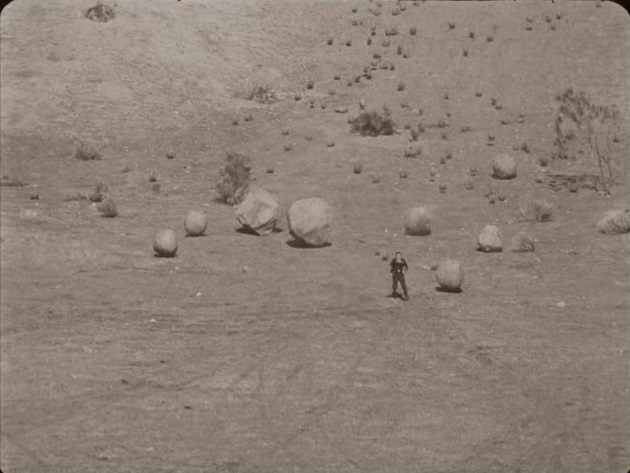

Porco Rosso is one of the few films directed by Hayao Miyazaki in which the historical and geographical setting is clearly defined and gives the director a chance to indulge in his Europhilia with the film’s picture postcard scenes of Italy and the Adriatic Sea. Academic Chris Wood states in his article “The European Fantasy Space and Identity Construction In Porco Rosso” that the film can be understood as a representation of wakon yōsai (Japanese spirit, western learning) – a tendency, since the Meiji period, for Japanese artists to paint Europe in a spectacular manner, while simultaneously maintaining the distance necessary to preserve a distinct sense of Japanese identity. Chris Wood states, “[In Porco Rosso] Europe is tamed, rendered as a charming site of pleasurable consumption, made distant and viewed through a tourist gaze“. So yes, Hayao Miyazaki is a European otaku. If there is a scene in the movie which captures this beautifully then it has to be the flashback to a young Porco (or Marco as he would have been known before his curse) and his longtime friend Gina lifting an early seaplane into the air in this display of pure unabashed nostalgia which captures the human desire to fly (thanks in large part of the enchanting music score by Joe Hisaishi). Likewise, one of the film’s most striking scenes has to be the flashback to Porco’s near-death experience and the origin of his curse. In this otherworldly sequence following a battle near the end of the war, Porco found himself in what the film describes as cloud prairie (I can’t find any reference to this term outside the movie), in which fighter planes from other nations rise above him into the sky as if there are entering heaven. The scene has similar vibes to the stairway to heaven from Powell & Pressburger’s A Matter of Life And Death while the use of synthesizers in the music score really makes it all the more captivating and eerie.

Porco Rosso is set during the final days of the roaring twenties and upon the onset of the Great Depression (“Farewell to the days of fun and freedom in the Adriatic”). The film’s setting also partakes in alternative history in which the wider Mediterranean Sea is beset with air pirates (albeit highly incompetent air pirates as reflected in their comical, circus-like theme music). From a romantic point of view it’s sad to say that air pirates are not real bar one incident in 1917 in which a civilian Norwegian schooner named Royal was boarded and captured by a party flying a German Zeppelin L23 – is the closest we’ve ever come to having steampunk fantasy become reality? As far as coinciding with actual history, Porco Rosso takes place during the days of Mussolini’s Italy as marchers in the street wave blue & green flags with bankers wearing the same design as armbands (this flag itself is fictional and was never an actual historical Italian flag). Porco is put under pressure from a former WWI comrade to join the state’s military to which he responds with the line “Better a pig than a fascist”. More sinister is the scene in which Porco pays off a loan at the bank and the teller asks him if he will invest in a patriot bond which of course, is only voluntary (wink wink). Despite its backdrop, Porco Rosso remains a largely apolitical film but if anything it shows that even under authoritarianism, life goes on.

The semi-love interest of Porco Rosso comes in the form of the pure feminine grace that is Madame Gina, of whom every flyer in the Adriatic is in love with as Fio claims. A longtime friend of Porco and his now deceased comrades, the film presents her as being “one of the guys” while not sacrificing any of her womanly demeanour. She will quickly run to a boat in a feminine stride but will make an epic and lengthy jump off the boat back onto the pier if required. Gina will dress to exemplance, even when in private and I do have to question if any particular Golden Age Hollywood actress is modeled after her? I am getting Mary Astor vibes myself. Gina occupies the island hotel known as the Hotel Adriano although it’s not made clear in the original Japanese version if she actually owns the establishment however, in the English dub, she refers to the place as “My restaurant” and the private garden as “my garden”. Regardless, the establishment is where all the hotshot flyboys of the Adriatic hang out where they kick back, relax and listen to Gina sing songs of lovers long lost. Like Rick’s Café Américain in Casablanca, there is an unwritten truce between all men. In the clouds, you may be enemies but at Gina’s place, everyone is your buddy. In her introductory scene, Gina shows little emotion in relation to having been told the news earlier in the day that her third husband had died in a flying accident, which as seen in films like Only Angels With Wings, was the norm in the early days of aviation. Porco and Gina share a “beauty and the beast” romance in which they never verbalise their feelings towards each other but you can tell there is a deep affection between the two. The other major female presence in Porco Rosso is the young Fio Piccolo, the counterbalance to Porco’s bleakness (and whose grandfather appears to be related to Hans Moleman). Porco doesn’t trust her to design him a new plane due to her being young and a girl says she understands this and doesn’t take offence. Rather Fio is aware that she needs to prove herself to him instead of just dismissing him as a sexist, well, pig (“Forgive my sins of using women’s hands to build a warplane”). However, it is somewhat odd the film concludes with narration from Fio’s point of view when this never happened at any other point in the film.

Porco Rosso does have one of the better Studio Ghibli English dubs, especially with the casting of Michael Keaton as the titular swine whose voice talents perfectly capture the world-weary cynicism of the character. I also enjoy Brad Garrett as the dopey pirate Capo while the announcer aboard the cruise liner as its being attacked by pirates adds some great deadpan humour to the proceedings. The sound mix of the dub is inferior when compared to the original while the lack of any reverb on the voices during the flying sequences is slightly jarring. Gina’s cover of the French song Le Temps Des Cerises is also re-recorded although there was no need to do so and I do consider the vocal performance on the original to be superior. Be that as it may, it’s Cary Ellwes’ southern drawl for the Errol Flynn-esque Donald Curtis which really add extra character to the dubbed version (in the Japanese version he is from Alabama whereas in the dub it mentions he is from Texas). The quasi villain of the picture, Curtis is a Hollywood actor who on his down time like Frank Sinatra, appears to converse with outlaws, while his delusions of grandeur thinking he will become President Of The United States with Madame Gina as his First Lady does make him somewhat endearing. Curtis does attempt to kill Porco by taking out his plane only to later discover his attempt was unsuccessful, eventually leading to the picture’s finale in which the two men sort out their differences through some mono e mono (in which Porco doesn’t even remove his glasses). I understand the psychological aspect of men making amends and even becoming friends after engaging in hand-to-hand combat, but Curtis did literally try to murder Porco earlier in the film, but I digress. Porco Rosso is another breed of artistic excellence from Studio Ghibli, you uncultured swine.

![Porco Rosso [紅の豚/Kurenai no ButaPorco] (1992)](https://satinyourlap.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/1118full-porco-rosso-poster.jpg?w=300)

![Castle In The Sky [Laputa: Castle In The Sky/天空の城ラピュタ/Tenkū no Shiro Rapyuta] (1986)](https://satinyourlap.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/laputa-castle-in-the-sky-japanese-original-vintage-poster-sku55326386_0.jpg?w=300)

![A Geisha [祇園囃子/Gion bayashi] (1953)](https://satinyourlap.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/800px-gion_bayashi_poster.jpg?w=300)

![Kiki’s Delivery Service [魔女の宅急便/Majo no Takkyūbin] (1989)](https://satinyourlap.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/2-1.jpg?w=300)

![Ocean Waves [I Can Hear The Sea/海がきこえる/Umi ga Kikoeru] (1993)](https://satinyourlap.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/ow2.jpg?w=300)

![Late Spring [晩春/Banshun] (1949)](https://satinyourlap.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/flyer_large.jpg?w=300)